Articles on Manohar Kaul

Writings Reflecting on His Art, Vision, and Legacy

A curated selection of essays, interviews, and tributes that explore the life, work, and influence of Manohar Kaul. Written by fellow artists, critics, and scholars, these writings offer diverse perspectives on his creative philosophy, visual language, and enduring place in the landscape of modern and contemporary art.

Manohar Kaul – Landscape Painter

By R. DE LOYOLA FURTADO

Amidst the welter of all the cliche-ridden bromides from the palettes of our painters, it is refreshing to find that in Manohar Kaul we have a landscape painter whose work is pregnant with a forth-rightness uncluttered by cerebration. For Kaul, art is simply a means for communicating joy, an experience charged with the wonder and the mystery of nature in all her vagaries.

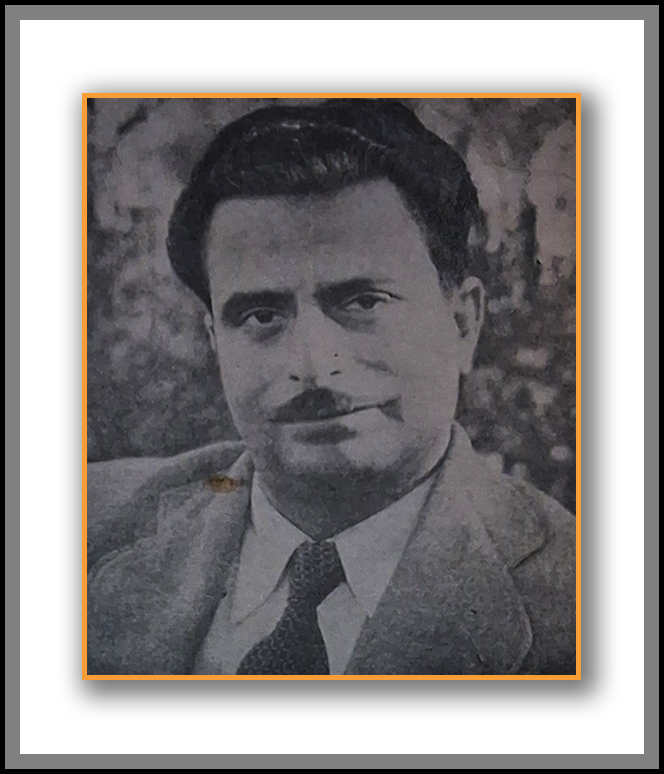

Photograph of Manohar Kaul, circa 1957

A water-colourist who has not deviated from tradition, Kaul imbues his paintings with a luminosity which enhances the enduring qualities and the integrity of nature. The still waters and the brooding silences of the Kashmir woods are elements which the artist has interpreted with warmth and realism without succumbing to any specious abstraction, although abstraction does exist in his forms. His paintings are decorative in the same sense that a Corot is decorative on a drawing-room wall. Kaul's art is free from all arty pyrotechnics. It is simply a spontaneous translation of the artist's attitude towards the perennial flux in nature, a deliberate search for plastic values in the ordinariness of things. But hidden behind this seemingly common-place material, there lies the revelation of a deeper significance, of unsuspected tonal gradations, and beauty which is perceived only by a discriminating eye. These delicate nuances of light and colour—their very pristine essence—lend themselves admirably to interpretations in the difficult medium of water-colour. And Kaul has caught them with an incessant precision, sometimes with a transparency metallic and hard, and still his paintings pulsate with an inner dynamism. The sense of duration is always there, and the paintings are always art. They are not synthetic bits of prettiness.

Summer glory, winter's grey desolation, the burgeoning of the spring, rain—these are the multiple faces of nature which Kaul has arrested in their singular innocence, their portentous depth and dream-quality.

Although he holds the degree of Master of Arts in economics and is not a painter by profession, Manohar Kaul studied fine art at the Amar Singh Technical Institute at Srinagar. He has also passed in the first class the examination in painting of the City and Guilds Institute, London, and is an art critic. His recent exhibition in Delhi inaugurated by Dr. Keskar was one of those occasions when the visitors left the gallery with a new awareness, which in turn brought the serene acceptance that the paintings were works of a serious artist.

The landscapes lingered long in the minds of those who saw them. There was nothing disturbing in the paintings. They were simply creations of a sensitive and ordered mind, which had recreated the facts of nature with a gentle yet austere lyricism. And behind the seemingly effortless ease, there were signs of a steady hand which is guided by an accomplished, fastidious and lively imagination.

Manohar Kaul

By Keshav Malik

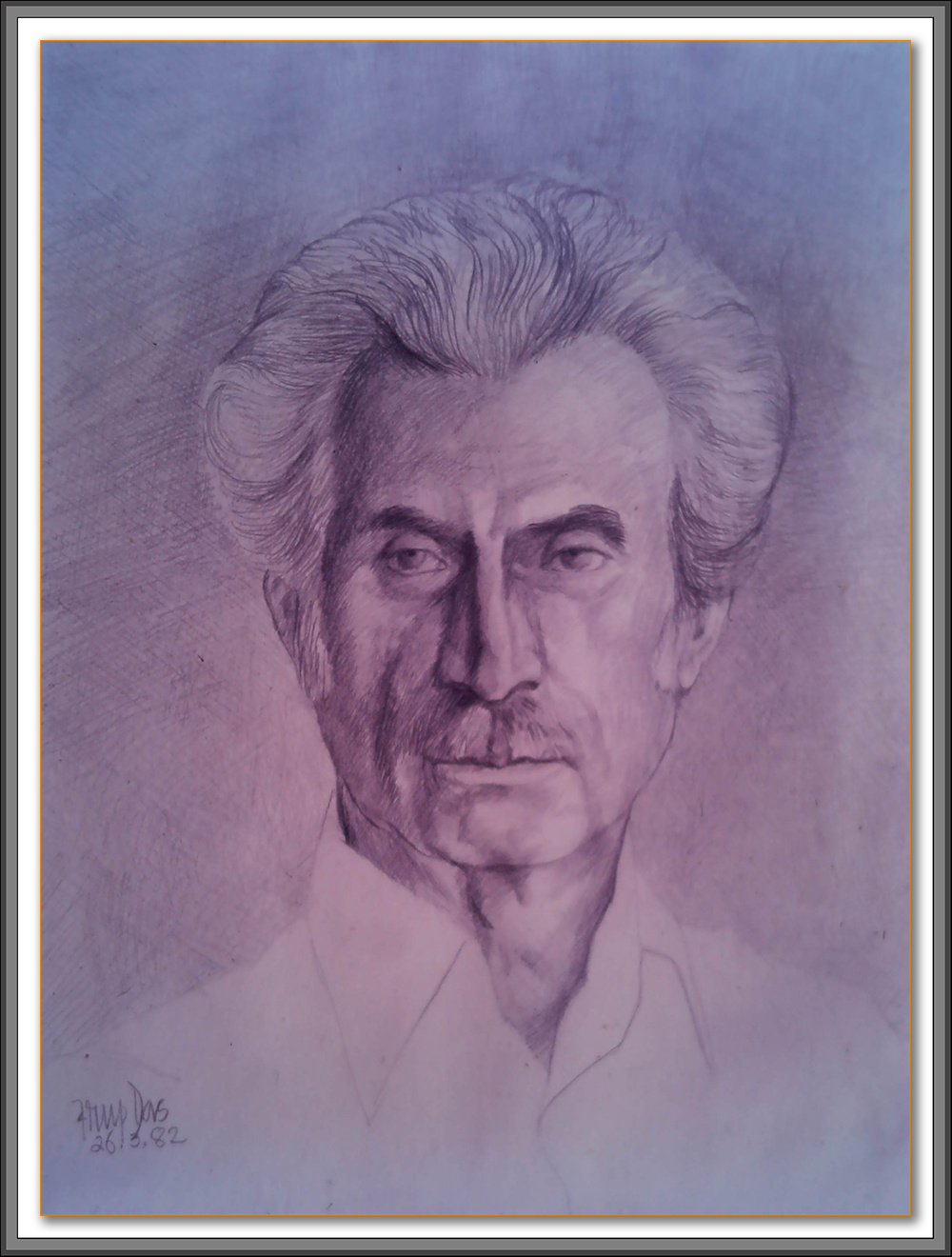

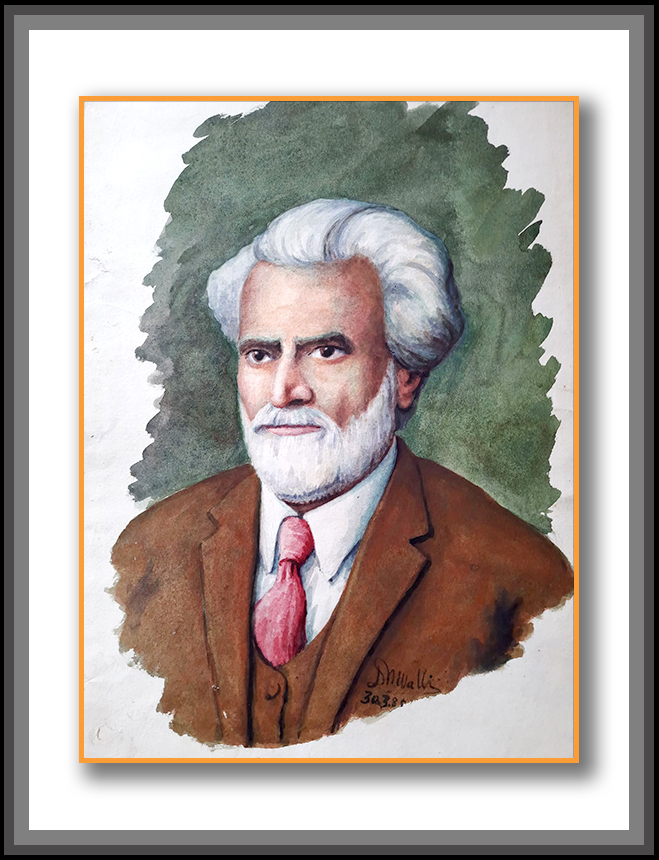

Portrait of Manohar Kaul by veteran artist Arup Das, 1982

Even as I think of Manohar Kaul and his work, I cannot seem to put aside the album of my personal memories of him (and Kashmir) and be simply 'objective'.

I relive with him his early days in Srinagar. I too nostalgically remember Sir Amar Singh Technical Institute and the bucolic principal J.C. Mukerjee. Then one goes on to remember Amar Singh College and the vivacious Prof. Madan, for instance. One remembers the springs and summers, autumns and winters of Hazuribagh with its long lines of Chinars (cut down to make a sports stadium); the merry mulberry trees, and the silk worm by the silk factory; the snow-line and the moving waters of Vitasta; the smell of wood in the doonga (freight boat) carting logs; flower and grass growing roofs; Hari Parbat at dawn and dusk; the seven bridges: vistas of populars; ruins of the marvellous black-limestone temples of Avantipora, Martand and others; saffron fields of Pampore in autumn; the holiness of the waters of Sheshnag; gubbas; namdhaas, papier mache and the wood crafts; walnuts, almonds and the slow pheran walk; the limpid lakes; the concentric circles on the waters; the gay exhibition grounds; Mahjoor, Azad and Nadim.

Infinite and undying the nostalgia. Does not sentiment become sentimentalism! But then, in the hands of some of the artists - Somenath Butt, D.N. Wali, P.N. Kachru, Trilok Kaul and others, the nostalgia led to art.

So, too, Manohar Kaul. What he was nursed on got deep into his blood stream; the mountain ranges became a part of his breathing. Here was transmutation of nature into art. One did not know this unfolding then. So the more pleasant the surprise. His art as well as his ideas on art developed, culminating in his volume on art - the first ever that really touched on the modern period. And thus all through the fifties and sixties he pondered and wrote on ancient, medieval and the modern periods - reviewing art books for newspapers and journals. The processes of the creation of folk art, as also those of general culture and aesthetics came in for his scrutiny.

These words prove that Manohar Kaul was neither 'anti' west nor overly 'pro' east. All he had was horse-sense in ample measure. For him only that art could be meaningful which was born in response to the given environment.

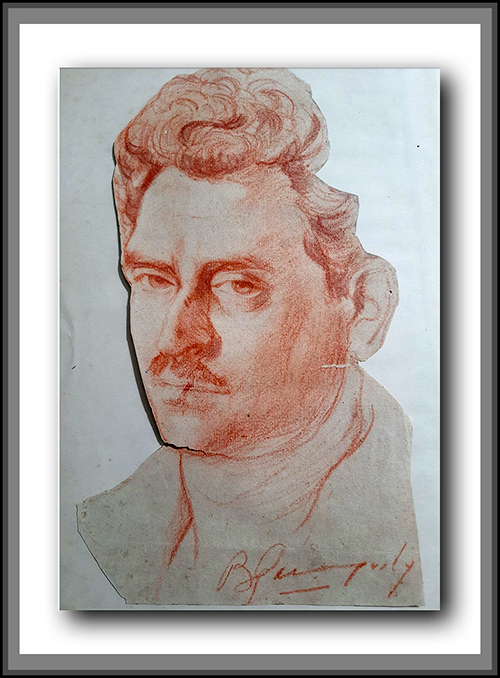

Portrait of Manohar Kaul

On his Trends in Indian Painting (published by Dhomimal's) said Vijayatunga in The Sunday Standard of November 17, '61 "He (Kaul) challenges and questions alian values. Either we agree or disagree with the author. He has fulfilled the task that had to be done."

Yes, Manohar Kaul's views in his reviews and articles of the fifties and sixties invariably have that same challenging feel as above. He was wisely able to, thus, evaluate contemporary art trends in the light of the earlier arts (Ancient, Folk, Moghul, Pahari, Rajasthani); and this was a far better perspective than an aesthetic of a pastless present, as with many others of the day.

That much, briefly, as far as the writer in Manohar Kaul is concerned. And now the artist in the man. One could not decide as to the virtues or otherwise of this apparent oddity one way or another, except by 1004ing at the actual work done by the artist during the four decades and more. Yes, Manohar Kaul risked being forgotten as a painter by the artistic community as well as the general public; or else to be remembered only for his paintings - the mountainscapes.

If that were all to show or if there were no artistic development, there would be little point to pen this piece. But, as it proved, the body of the artist's recent work testifies to the fact that the man had been labouring all through, and steadily and he has grown out of his simplistic mountainscape to compelling studies of forms and shapes of the world. The nature in his mind's eye had become increasingly more refined - each new work climbing upward on the shoulders of the preceding one. Here was no 'made easy' landscapes but distilled essence. The artist tried to catch the gravity in what met his eye; not large views but delimited ones - closeups; stone and crystals; the rocky substance of the planet earth; glacial purity; the flowing white between dark rock; piled up volumes; in all their ebony and ivory immensities; the contrasting red and white of the stone flowers; slices of sky; crisp inscapes of narrow gorges; the soft of green vegetation against sharp geologic nibs and 'tombs' stones; nature's pyramids; white against mist; the geometry of ranges, spectral light; the near humanized vertical rising stalacite forms; the wrapped up presence of inscrutible lingams; chaste snows; winding, cloud-enveloped peaks; rare altitudes; the snowy moon; the contrasts of hard and soft colours; mysterious air; pertified mythic forms; oval shapes of jade green stone; occult gypsam forms; the majesty of denuded trees set against optical patterns and designs; divinity lurking in the recesses of rocks; cold waters and the new moon;

The seens insist that the world is a stranger

seeing immensities in mist,

hearing the breathing of gods

in recesses of rocks

That is what Manohar Kaul's work, at its peak conveys through the usual craft of brush and easel; the sensuous element is employed to communicate life truth; to convey the presence at the heart of the world of something profound; above the din of mundane existence, the ice-cold light:

I arrive at the flaming circle of vision

when at once is touched the centre

of my live nerve

with blinding revelations.

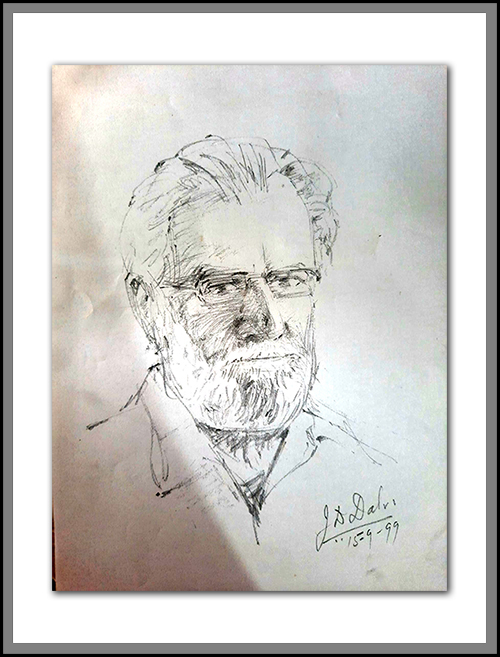

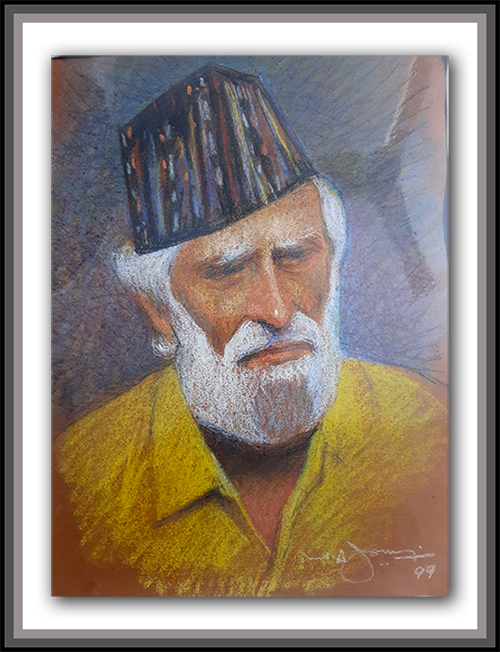

Portrait of Manohar Kaul by veteran artist J.D. Dalvi, 1999

Such revelation comes via the hardest of material - sculpted rock and ice. There is, surely nothing wishy-washy in such aspirations:

rock, true-packed

with substance; the arms of trees

twisting in mortal effort;

an earth that continually

turns face

to face the presiding sun

A miraculous prospect, one dreams it like a blissful dream; the mystery of reality - the heart of solitude. It is a sort of self-surpassing that the seer hankers after, a self surpassing that makes the seer, composed and calm and wise. The holiness of the painter vast ranges is suggested in these lines:

No shout heard -

at most a soft pin-drop,

or perhaps an alpine bird in the quiet

but outside these no third

At this point in time Manohar Kaul had a clear conception of what art was all about, as of its place in human life. He did not accept things docilely but argued the pros and cons carefully.

At this point in time Manohar Kaul had a clear conception of what art was all about, as of its place in human life. He did not accept things docilely but argued the pros and cons carefully.

The growth of mind as well as the tenacity to hold on to native points of view were refreshing; to agree or not with his views being only secondary matter. Manohar Kaul may well have been taken for an aesthetic reactionary or chauvnist then, if so, the indictment appears wholly unfair. In case he erred in emphasizing the importance and value of earlier art, the meaning of his emphasis becomes palpable even as we are now rudely made aware that today it is the Indian artistic tradition which is disadvaniaged, not western implantations in India.

While the Rodin show in Delhi a while ago was visited by the generality of artists, quite as they ought to have done, the superb, all important show of South Indian Bronzes, at the National Museum, was hardly seen by most-artminded locals. Surely, those bronzes are a high water mark of Indian genius and aesthetic sensibility. But apart from some discerning 'culture' people - Indian and foreign - others were unaware of the riches in their midst. No wonder. After all, schools, and colleges of art do not any longer offer lessons in line with the older methods and only go for life modelling. Necessary as the last are they are all too limited. The non-muscular human body is no longer understood by the public, and even some artists. One sees people hankering and doting in museums over second-rate copies of Greek art for their virtues of life-likeness than on the imaginative, only suggestive freizes of Indian temples. It appears, the 20th century foreigner may have a deeper understanding of a subtler art than the native does. In his sense Manohar Kaul foresaw artistic piffalls ahead-of most of us. His insistences were understandable. There were those, then, who leaned heavily on the side of the international ovement and others who went straight for an imitative Indianism. Manohar Kaul did not over-do this Indianism. To quote him from his piece in 1962 on Satyen Ghosal's work: Endowed with a balanced mind Ghosal withstood, rocklike, the buffets of the swelling trends from the East or the West, but felt and tested each one of them, and assimilated their individual essence into synthetic pattern of his own."

He after having a solo show in fifteens, he put up a group show in 1983 covering his works of three decades. After this there was no doubt non stop creative works of the artist.

Manohar Kaul, like all nature poets knows:

There is a singer at the heart of the old earth.

and that: ever the sun shimmers upon inland peaks and lakes

the moon waxes silver in his dark wake;

there is some one, a spirit,

whose joy is the infinite......

And he has therefore struggled to express only:

the tallest ranges

and the diamond fires

on sub-blinded Wulars.

Manohar Kaul's genre is of course varied - except for some portraits. The painter has struck to his original inspiration, he has been only true to himself. His is a work only of joy, but perhaps, joy is the supreme quality in art. Manohar Kaul's highest peaks are likely to remain unshakably secure in the mind's eye. Recently he has introduced light in his Works and has also stressed on the changing effects of the environment and atmosphere.

It may be interesting to add that the painter has also put his inner knowledge of colours and precious stones to curative uses. He brings the healing touch to those who come into his contact.

MANOHAR KAUL'S ART: NEW DIMENSIONS OF ITS VISUAL DYNAMICS

By Narendra Dixit

A large number of Manohar Kaul's recent water-colour landscapes, lately exhibited in one of the AIFACS galleries, is a body of his creative output that rightly attracted attention of the Delhi Art Circles. With these he arrives at the point in his artistic career, where he readily establishes his reputation as a significant painter, joining the rank of the best in the genre, and in many instances, excelling even these. But where he excels, he tends to modify the genre itself, often reducing the forms of nature to an abstract configuration - dynamic pattern of elemental forces in action.

portrait of Manohar Kaul, 1999

Corporeal entities of nature as depicted in these works appear metamorphosis As they become elements of visual dynamics. Void becomes an active formal agent, acquiring the range of a cosmic dimension, and frequently, a resplendent aura glows through in the midst of an otherwise somber expanse.

These works of Manohar Kaul, however, gain more in significance when viewed in the context of his earlier works - landscapes painted in oil on large canvases. Some of these early canvases, painted some time in 1980-81, possess an ambience of an other would be apparent.

The layers of paint applied on the canvas have a smooth translucent body - possibly laid over with a transparent glaze - with the predominant use of various shades of the pale blue and pale green colours, imparting these canvases an impersonal quality as that of an antiquated porcelain vessels. Rock and mineral formations, foliage and plants, distant hills with a chunk of luminous sky overhead and expansive valleys - all these as the components of the pictorial imagery possess a phantom like presence, at once shadowy and unreal.

Oil paintings on Himalayas of eighties, called "Laddakh landscape" (obviously painted in the artist's studio in Delhi from the nostalgic memories of that enchanted land) appears as a place in trance. The entire canvas is painted in pale colours of various hues - mainly greens, blues and browns.

Distant pale hills are disposed against the pallid horizon, painted in the dull emerald green, and an apparition like island, with a cluster of the building blocks of variable sizes, appears to be melting away in the surrounding mist of the sprawling valley. In the foreground, on the right hand top corner of the canvas, loom large enormous dark green blue foliage with its fangs-like leaves and a bud-like shape of an equally menacing presence and dimension, on the left. To look at this painting, indeed, is to traverse into the borderland of mysterious environ.

Another canvas of the same period of an oblong shape and vertically oriented, is painted in soft blues, pale yellows, and light browns. Gentle slopes of the greenish pale hills undulate in the background and the way shape of their contour echoes in the cloud formations above in the sky. In the otherwise murky ambience of the scene, glistening make it look rather. And this effect is further accentuated when lucent silver-lining of clouds in the sky, instead of illuminating the landscapes, appears rather portentous and imparts it a quality of luridness. This lurid sparkle of highlights spart, the whole atmosphere of the scene looks leaden and cold as if it were jinxed by some unknown curse.

We find in the water colours of late nineties, a process of dialectical leap in Kaul's artistic career. The corporeal world as depicted in these water colours is as unsubstantial as ever but elements of their visual dynamics as also the configurations this dynamics gives rise to, are as palpable and appear as real as anything or any dynamics process that is caused to precipitate in the material world that surrounds us. Nature as shown in these water-colours is a configuration of elemental forces at play. The result in some cases is a turbulent world, where nothing seems to be settled as if in a state of Twix.

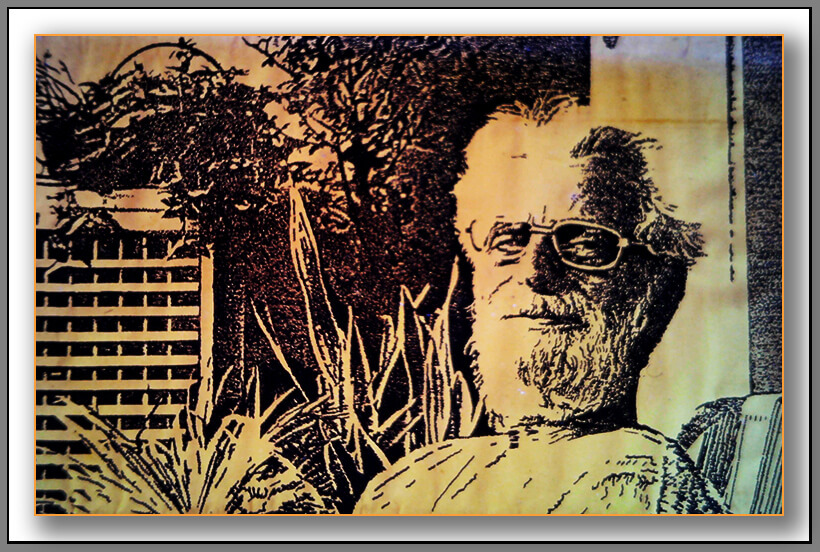

Irresolution or rather a precarious resolution of contending forces and shadow existence of objects as represented are two prominent characteristics of Kaul's water-colours. The former is essentially the prominent feature of his water-colour landscapes, whereas the latter is also an indispensable characteristic feature of his earlier oil paintings of eighties. Kaul, by temperament, is a spiritually inclined person and, perhaps, he himself identifies this austere quality of impersonal remoteness and immateriality of imagery, as depicted in his early oil paintings and subsequently in his water-colours of nineties, with the spiritual contents of his art. Strangely enough, his own photographic content of his art. Strangely enough, his own photographic portrait, reproduced in the catalogue of his last exhibition held at the AIFACS gallery, is characterised by a kind of a ascetic presence. Or rather, this photographic image appears as the astral counterpart of his corporeal existance. Surely, Kaul is not an out going person. He is withdrawn by nature. Certain cool aloofness characterises his personality itself. One however, may wonder whether this trait is due to his inherently shy nature or to his spiritual bent of mind, may be both or because of his deep involvement in his own creative world.

Portrait of Manohar Kaul by veteran artist D. N. Wali, 1985

Back to his art again. Calmness, remoteness and immateriality could be traits of a kind of spiritual art. But "turbulence" could equally mark the spiritual strivings of man. Manohar Kaul's calm façade can successfully - but deceptively - conceal his inner energy and restlessness, and of which this author had a glimpse, while seeing his paintings in his studio, when Kaul would intermittently repeat: "To painting is a must for me, with despite my editing of "Kala Darshan" or paintings. Stepping out of the charmed circle of his earlier paintings of eighties, he join in, "the thunderous collision of different worlds" of Kandinsky, as he starts painting his water-colour landscapes. The turbulence of these recent configurations in water-colour provides an "isomorphic equivalence" of his inner restlessness. The most striking features of these configurations, however, are the handling of luminescence by the artist and his treatment of space.

Luminescence is not the reflected light. It is a state of energy caused by certain cosmic events taking place at a point in space-time continuum. Kaul's water-colour configurations, if anything, appear to be configurations of these events with luminescence as their inseparable part. Luminescence here, indeed, touches upon the sublime and space of these configurations, instead of providing a neutral back-drop for such events to take place, appears to become an active force - the one among others - with time as an added dimension. Such events of cosmic nature are given rise to by the forces of nature in action, and forces of nature become palpable only through such cosmic events. Nature in Kaul's water-colours is not an ossified object or a configuration of such objects to be meditated upon. It is a play of forces in all its splendour - Leela. And luminescence, indeed, appears as its crowning glory.

Sources of luminescence in Manohar Kaul's turbulent landscapes appear in many forms and many ways - sheets of translucent snow covering the mountain slopes; frosty white streams and brooks meandering through narrow gorges, deep ravines and swarthy valleys; crystalline surface of a frozen pool gleaming some where in a yawning dale; and apparition like hoary-white mist rising above, in sprawling murky valleys. Nature, in all its glory, is made palpable in many modes and many moods.

In one of these small-format water-colours, an enormous mass of crystal like transparent rock formations, occupying the major portion of the pictorial surface, is delimited on top by a sagging horizon-line. While a fragment of the turbulent sky, in its kaleidoscopic mode with effervescent clouds, appears to hover above the colossal cliff below, with its broody somber presence. Despite the enormity of its formal propositions, this shimmering mass appears to be of an incorporeal nature.

In another one, a strip of the nondescript sky, tinged with a stains of pale yellow colour, overhangs the yawning stretch of land below. This swarthy expanse of land is cleaved and relieved by a horizontally disposed, straight narrow band of a stream, aglow with its silvery white aquatic surface, resembling that of a highly burnished metal mirror. The radiant stream, in the midst of the murky surroundings of the abysmal depth of a gaping land-mass, indeed, touches upon the sublime.

Manohar’s “Kaulscape”

By Vasantha Iyer

“I would like to confess that I achieved something which is worth the wealth of the whole world — peace of mind.”

When Manohar Kaul, Chairman of the All-India Fine Arts and Crafts Society (AIFACS), makes such a claim, one cannot but admire the tenacity with which he has coped with and overcome many obstacles in his life. His sustained hard work and vision are evident in everything he has accomplished.

Poster artwork of Manohar Kaul for 'Help Age' exhibition, early 1980s, by Ritu Sharan, artist and daughter of Manohar Kaul.

If change is the essence of life, Kaul has welcomed every change and transformed it into valuable experience. At the age of about ten, he was told by a darvesh or faqir that he was the adopted child of his present parents. Kaul was not alarmed; instead, he recalled how his (adoptive) mother used to take him to receive blessings from a naked faqir who smoked a pipe non-stop, and to whom people of all faiths came to pay their respects.

Kaul hails from a religious family that lives by the faith of the ghar devta, the household deity. At the age of six, he had a mystical experience—he saw a vision of the ghar devta entering the house during his father’s recitation of sacred verses. Even as a child, Kaul would draw and paint on whatever surface he could find, even the ground.

As early as 1931, he witnessed gory bloodshed between Hindus and Muslims in Srinagar. The atmosphere at home became increasingly “suffocating” because Kaul was not allowed to study the arts, such as painting and music. Though his adoptive father was a learned man, he shared the common contempt for artists.

A great deal of misunderstanding led to Kaul’s parents arranging his marriage at the age of 17 to Mohini. This teenage marriage proved to be a turning point in his life. Mohini understood Kaul’s aspirations and supported his studies and artistic pursuits. However, parental interference continued and caused much anguish to the young couple.

Despite these challenges, Kaul began painting the grandeur of the Kashmir landscape. Even in recent years, he has exhibited characteristic Kashmir scenes, which an art critic once described as “Kaulscapes.” These miniature-format paintings, featuring snow-covered mountains and golden mustard fields, transform the lush green Kashmir landscape into bejewelled works of art.

Kaul eventually came to Delhi seeking opportunities in painting and writing. His articles and paintings were well received, and his book Major Trends in Art was warmly acclaimed. In Delhi, he became Assistant Editor of Our India. Later, he was selected by the Union Public Service Commission for the Central Information Services, where he held many important assignments and was known for his sensitive approach and notable achievements.

Valley of the Gods

In “Valley of the Gods,” it is the unforgettable landscapes of Kashmir—insatiable and tantalizing even without the moon—that captivate the viewer. These landscapes, often drenched in moonlight, cast a romantic ambience. The valleys and woodlands retain their pristine glory, both as they once were and as they now exist in Kaul’s dreams.

The present violence and destruction are not even hinted at—Kaul insists on remembering Kashmir as a veritable heaven on earth.

Kala Darshan and Art Criticism

As a continuation of Our India, Kala Darshan became an exclusive art magazine run single-handedly by Kaul. It also served as a platform for “art criticism” that was particularly useful for young artists. He had earlier edited Art News, and authored the book Kashmir: Hindu, Buddhist and Muslim Architecture.

Manohar Kaul is deeply interested in spiritual phenomena and is reputed to be able to read palms and horoscopes. Of himself, he says:

“During my career of nearly four decades, I have been strictly guided by my personal psyche and painted only what I was inspired to transform on canvas. I have not allowed myself to be lured by passing fashions or the craze for recognition.”

Kaul speaks of a close communion with ethereal aspects of nature. His main emphasis has always been to highlight the sublime elements inherent in the Himalayan ranges—their glory, the unique textures of rock formations, and how they come alive in celestial light.

Kaul’s Role in AIFACS and National Art Policy

Though controversial some time ago, the AIFACS is now steering in the right direction—barring occasional cultural friction with the Lalit Kala Akademi. A nominal pension is provided to elderly artists. Art competitions are held for youth, women, the handicapped, and for national and international artists. Scholarships and grants are awarded, and artists are sponsored to hold exhibitions.

These are small but significant steps toward preserving and promoting art and culture in India.

Kaul brings to his chairmanship of AIFACS a lifetime of experience in painting, spiritualism, authorship, administration, and art criticism.

Themes and Medium

Watercolour, with its translucent transparency, is his favourite medium. Kashmir, with its ethereal beauty, is his perennial theme. Whether the series is Mystique of the Moon, The Radiant Sun, or Dawn in Kashmir, Kaul’s work always evokes wonder and reverence.

Manohar Kaul – Landscape Painter

Kaul brings alive dead pretty Kashmir

By Ratnottama Sen Gupta, Art Editor, The Times of India (Jan. 1995)

What it be? Sea, land or sky! Shall he praise the beauty of the wind among the derelict fields, or kneel before the breathtaking spirit of silence reigning supreme in the downward dive of a snowy giant's high?

The poet in Keshav Malik penned the lines for Manohar Kaul. Both of them treasure the memory the youth spent in the valley at the foothill of the Himalayas. Kaul would go rowing in the Dal lake with friends and "before we realised, it was two in the morning!" The icy stream killing the stillness of the luminous night, the rows of chinar standing guard at the horizon; the silvery crest of a crescent moon; the world bathed in the purity of the snowflakes: indeed, they looked no further for paradise.

Decades down the winding course of life, Kaul draws on the memory of the ethereal landscape that was his home. The valley lives on in its pristine glory: the woodlands have not lost their leafy haze; the misty mountains are suffused with tranquillity in the canvas of this painter approaching 70. After meditating on the Mystique of the Moon, his watercolours are now celebrating Auras of the Dawn in Kashmir.

Both the series are the fruits of Kaul's communion with nature, "recollected in transquillity and reproduced from imagination," he adds. If, earlier, the artist had used the watercolour medium to recapitulate the transformation of nature in the magic of moonlight, the current work is imbued with the meditative spirit of the day-break hour. The theme acquires a personal significance for Kaul as it did for the sages of yore, "all along my creative years I have worked at this amritvela (peaceful hour), when the atmosphere is so fresh."

Viewing the series at AIFACS, you may wonder why you trace no note of nostalgia, no tint of sadness in the exhibits. That, you may say, would be natural for one who roamed the valley when it was green. Now that it is pillaged and pained, should not the sensitivity of an artist's soul resonate the trauma that rents the milieu? No, asserts Kaul: that's the burden of a reported, an illustrator. "I cannot show a man killing another man," he pleads. But if he cannot show that, he can certainly depict the dream that is sure to dissolve in the harsh reality of destruction. "Also," Kaul hopes, "if people see how beautiful Kashmir is, their desire to retain it will be strengthened."

As a bureaucrat serving the ministry of information and broadcasting, Kaul had gone back to Kashmir in the early 70s."I could never think that the same men, who watched the surrender of General Niazi without any sorrow, could pick up the gun!" The boys have gone astray, he remonstrates.

Kaul's homeland was not only the paradise come to earth: it was of strategic importance to the nation, neighbouring as it did countries like China, Afghanistan and the newborn Pakistan.

Kaul, of course, is as much at home in the Capital which has seen him at his creative best. He has been busy, since he retired from the service in the '80s, bringing out the art journal Kala Darshan. Almost single- handedly, "I have even been the errand boy," he tells you. The experience has undoubtedly benefited the art fraternity, since it has helped Kaul revive Roopa-Lekha, the journal of the All India Fine Arts and Crafts Society (AIFACS) following his selection as its chairman.

In that capacity, Kaul has worked another wonder: the four galleries, which were once given up by artists for its derelic condition, are now among the best in the Capital. Besides, there are plans afoot to build up a library and a conference hall "as at IIC". The Society is expanding too: it has acquired buildings "at Ghaziabad, for the graphic artists and at Chandigarh too." It has ambitions of providing studio space to artists, "for six months at a time". Above all, it is honouring veteran artists - those above 60 - and giving them "a small amount of Rs. 3,000 per annum."

All this for the world of artists. And in the small hours of the morning, before the world starts making its demands on Kaul, there is the divine landscape which the artist carried within him when he left Kashmir behind.

Interview with Manohar Kaul

Originally published in Amar Ujala, 1993

"The artist must be self-critical. He should know himself and also know what he is doing. The independent existence of an artist can only be established when he understands his own reality and personality." —Manohar Kaul

Question: What is the biggest challenge facing today’s artists?

Manohar Kaul: The biggest challenge for today’s artists is how to connect with the reality of their own society. Blind imitation of Western art has severed our artists from their roots. They are no longer able to recognize the life of society, its sensitivities, and its needs.

Question: Is there a possible solution to this?

Manohar Kaul: A solution is possible only when artists engage in self-reflection. They must consider the society they live in and understand its artistic sensibilities. Only by connecting with their own experiences can they create something true and meaningful.

Question: Do you think today’s art is having any impact on society?

Manohar Kaul: Today's art has failed to guide society. The reason is that the dialogue between the artist and society has broken down. Until that dialogue is re-established, the significance of art will remain incomplete.

Question: How do you view today’s art education?

Manohar Kaul: There is a lack of seriousness in today’s art education. Art institutions are dominated by a commercial mindset. Students are neither being taught to understand tradition nor are they given the experience of creative freedom. As a result, they tend toward imitation.

Question: How do you see the government’s role in the field of art?

Manohar Kaul: The government's role has been limited and largely formal. The institutions meant to promote art often fall prey to favoritism and individualism. Until policies are made with a genuine understanding of art’s values and purpose, no meaningful change is possible.

Question: In your view, what should be the purpose of art?

Manohar Kaul: The purpose of art should not be limited to creating beauty—it should also make society more sensitive in character. What is needed today is that we draw inspiration from our traditions to create an artistic environment that fosters self-awareness and helps re-establish human values.

मनोहर कौल के साथ साक्षात्कार

मूल रूप से प्रकाशित: अमर उजाला, 1993

"कलाकार को आत्मालोचक होना चाहिए। वह खुद को पहचाने और यह भी जाने कि वह क्या कर रहा है। कलाकार की जो एक स्वतन्त्र सत्ता होती है, वह तभी बन सकती है, जब वह अपने यथार्थ और व्यक्तित्व को समझे।" —मनोहर कौल

प्रश्न: आज के कलाकारों के समक्ष क्या सबसे बड़ी चुनौती है?

मनोहर कौल: आज के कलाकारों के समक्ष सबसे बड़ी चुनौती यह है कि वे अपने समाज के यथार्थ से कैसे जुड़ें। पश्चिमी कला के अंधानुकरण ने हमारे कलाकारों को अपनी जड़ों से काट दिया है। वे अब समाज के जीवन, उसकी संवेदना और उसकी आवश्यकताओं को पहचान नहीं पा रहे हैं।

प्रश्न: क्या इसका समाधान संभव है?

मनोहर कौल: समाधान तभी संभव है जब कलाकार आत्ममंथन करें। उन्हें यह सोचना होगा कि वे किस समाज में जी रहे हैं और उसकी कला-संवेदना कैसी है। अपने अनुभवों से जुड़कर ही वे कुछ सच्चा और सार्थक रच सकते हैं।

प्रश्न: क्या आपको लगता है कि आज की कला समाज पर कोई प्रभाव डाल रही है?

मनोहर कौल: आज की कला समाज को दिशा देने में असफल रही है। इसका कारण यह है कि कलाकार और समाज के बीच संवाद समाप्त हो गया है। जब तक यह संवाद पुनः स्थापित नहीं होता, कला की सार्थकता अधूरी रहेगी।

प्रश्न: आज की कला शिक्षा को आप किस रूप में देखते हैं?

मनोहर कौल: आज की कला शिक्षा में गंभीरता की कमी है। कला शिक्षण संस्थानों में व्यावसायिकता हावी हो गई है। छात्रों को न तो परंपरा की समझ दी जा रही है और न ही उन्हें सृजनात्मक स्वतंत्रता का अनुभव कराया जा रहा है। परिणामस्वरूप वे नकल की ओर उन्मुख हो जाते हैं।

प्रश्न: कला के क्षेत्र में सरकार की भूमिका को आप कैसे देखते हैं?

मनोहर कौल: सरकार की भूमिका सीमित और प्रायः औपचारिक रही है। कला को प्रोत्साहित करने के लिए जो संस्थान हैं, वे भी अक्सर पक्षपात और व्यक्तिवाद का शिकार हो जाते हैं। जब तक कला के मूल्य और उद्देश्य को समझकर नीति नहीं बनाई जाती, तब तक कोई सार्थक परिवर्तन संभव नहीं है।

प्रश्न: आपकी दृष्टि में कला का उद्देश्य क्या होना चाहिए?

मनोहर कौल: कला का उद्देश्य केवल सौंदर्य की सृष्टि नहीं, बल्कि समाज के चरित्र को संवेदनशील बनाना भी होना चाहिए। आज आवश्यकता इस बात की है कि हम अपनी परंपराओं से प्रेरणा लेकर एक ऐसा कला वातावरण बनाएं जो हमें आत्मबोध कराए और मानवीय मूल्यों को पुनः स्थापित कर सके।

Majestic Himalayanscapes

THE TRIBUNE, SATURDAY, APRIL 30, 1983CHANDIGARH: An exhibition of 28 paintings of the Himalayas done by three well-known painters of mountainscapes - Serbejeet Singh, Manohar Kaul and Ramnath Pasricha - is on view until May 5 at the Government Museum and Art Gallery in Sector 10 here. First of its kind in the City Beautiful this show of Himalayanscapes has been organised jointly by the All-India Fine Arts and Crafts Society and the Punjab Lalit Kala Akademi.

Although realistic in style these paintings of our "eternal sentinel" are not trite faithful copies of Himalayan topography and atmosphere. They are contemplations on the inner force, the eternal/eerie majesty, of the Himalayas - and are re-creations inspired by deep personal knowledge, experience and vision of the individual artist.

The visual impact and power that these mountainscapes transmit to the viewer uplifts him from the mundane to a near-spiritual experience of the might and majesty of Mother Nature. It is possible to experience a feeling of being on the top of the world in spite of the fact that each painter has highlighted different aspects of the Himalayan scape.

SERENE MAJESTY

Serbjeet Singh works on a restrained palette with preference for ochres and browns. He dispenses with the human and animal figures as also other superfluities with monastic selectivity. He dramatises in his seven paintings by deftly leaving out large areas of unused canvas.

He unravels the serene majesty and placid timeless of the Himalayas by underscoring expansiveness of space and immensity of form. His mountainscapes seem to breathe effortlessly the spirit of inviolable freedom even when the whole canvas is nearly filled out. He leaves patches of white in strategic locations to create this sense of boundless-ness.

Manohar Kaul's 14 canvases range from the highly dramatic to the painstakingly studied. His palette is not restrained slopes, ranges and gorges with their configuration ensconced in mist - lose their geologic ruggedness and become etherealised for an enchanting aesthetic experience. His paintings are less austere and highlight the exuberant colourfulness of the Himalayan ranges.

Ramnath Pasricha also uses a less restrained palette, with purple as a recurrent hue. His mountainscapes range from mysterious vistas to cloud-hugged peaks which seem to float about in sheer say abandon. His emphasis is on the structural ruggedness of the terrain. There is a strange sense of perseverant bovaging through the poetic if somewhat frighteningly lonely, ranges of the Himalayas.

The Chief Minister of Punjab Mr Darbara Singh, attended part of the function

S.S. Bhatti