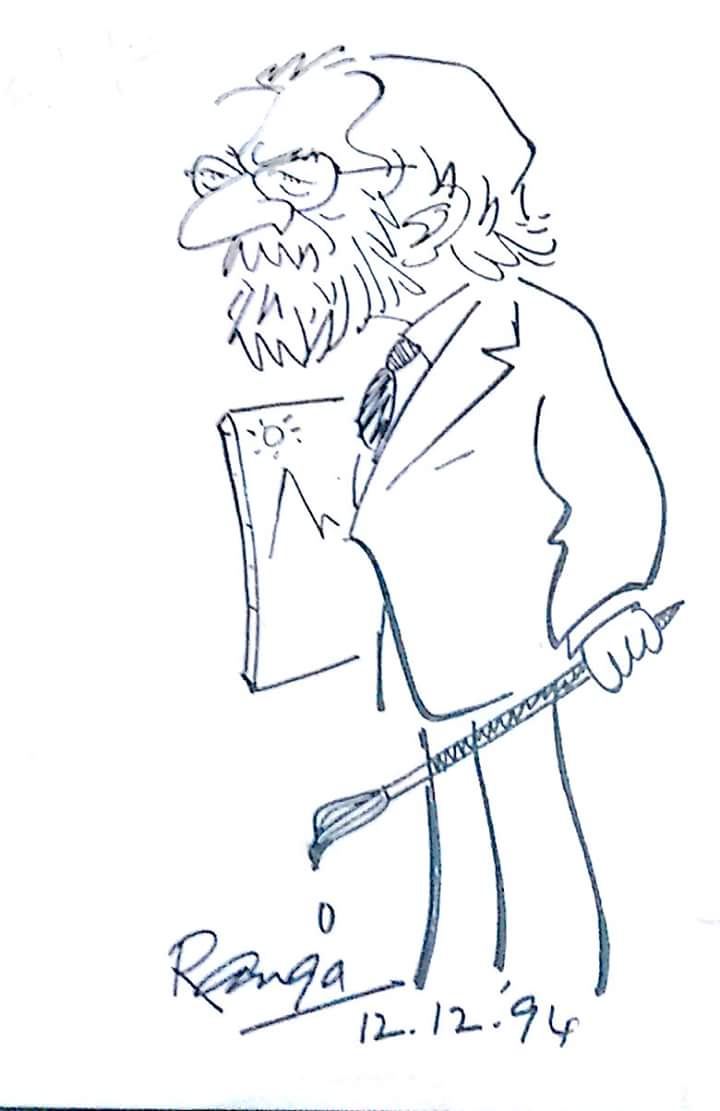

Caricature of Manohar Kaul by N. K. Ranganath (“Ranga”).

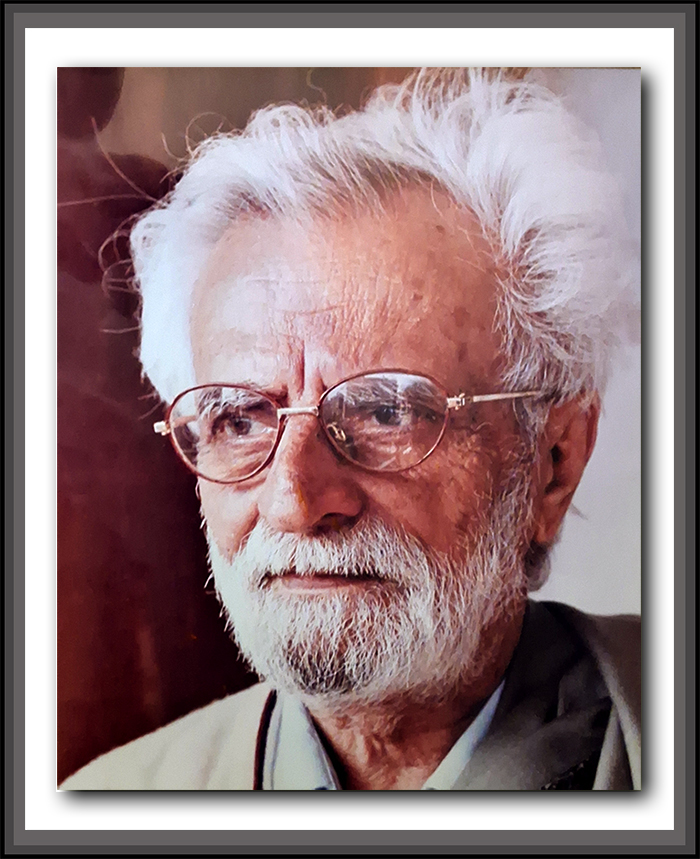

Manohar Kaul (1925–1999): A Luminary of Indian Art and Cultural Stewardship

Manohar Kaul, a distinguished Indian painter from Kashmir, forged a singular voice in 20th-century Indian art through his evocative mountain landscapes and profound engagement with Indian aesthetics. Born Manohar Nath Kaul, he later adopted the name Manohar Kaul as his artistic and literary identity—the name under which all his major works were published and exhibited.

Early Life and Education

Born on 21 September 1925 in Maharajgunj, Srinagar, Manohar Kaul was adopted in infancy from a financially modest household of his biological father into the well-off household of his adoptive father, who was likely a close cousin, though in Kashmir, such familial relations were often referred to as 'brothers' or 'sisters' regardless of the precise degree of kinship. This adoption, as the family lore goes, was divinely orchestrated. Both his biological mother and his adopted mother frequented the hermitage of a revered Sufi saint, a faqir, who resided in Ishber near Nishat garden, each praying for their unique aspirations: the biological mother for her husband’s career advancement, and the adopted mother for a child. The story recounts that during her pregnancy, his biological mother was instructed in a dream by the faqir to give her newborn to the adopted mother. When she shared this dream, both women reportedly laughed it off, attributing it to pregnancy fancies. However, during their subsequent visit to the faqir's hermitage, he, aware of their disregard, reprimanded the biological mother for not following his divine instruction and, taking the infant, personally handed the child over to the adopted mother. This remarkable turn of events profoundly altered the course of Manohar Kaul's life, diverting him from a path of potentially limited opportunities and instead opening doors to higher education and artistic pursuits—an aspect Kaul himself deeply attributed to shaping his unique direction.

Kakni, mother of Manohar Kaul

Raised as the only child in this home, he received early access to comfort, care, and cultural refinement, often pampered by his mother, Batni Chaman Vanmali—affectionately called Kakni within the family—and his maternal-grandmother, who resided with them. The family later moved to Rainawari, where his adoptive father built a house—partly to help distance him from his biological family and ensure a stable sense of belonging.

His earliest memories include the 1931 communal unrest in Kashmir, when his father carried him through the streets to safety amid violent riots. These early experiences of both privilege and vulnerability would subtly shape his sensibility as an artist and thinker.

During his formative years, Kaul studied at a Gurukul school in Gujranwala, in the Punjab region of British India (now in Pakistan). The institution was rooted in traditional Indian education and instilled in him a deep appreciation for Vedic philosophy, discipline, and holistic learning. He completed his matriculation there before returning to Kashmir, where he graduated from S.P. College, Srinagar.

Despite his deep interest in art from an early age, the pursuit was not initially supported at home. Some relatives discouraged the pursuit of art, persuading his father, Prof. Kanth Kaul, that it was neither respectable nor viable as a vocation. This created pressure on Manohar to suppress his creative inclinations. However, an art teacher of considerable standing recognized his exceptional talent and personally appealed to his father. Moved by this endorsement, his father relented—on the condition that Manohar continue to take his formal academic education seriously alongside his artistic training.

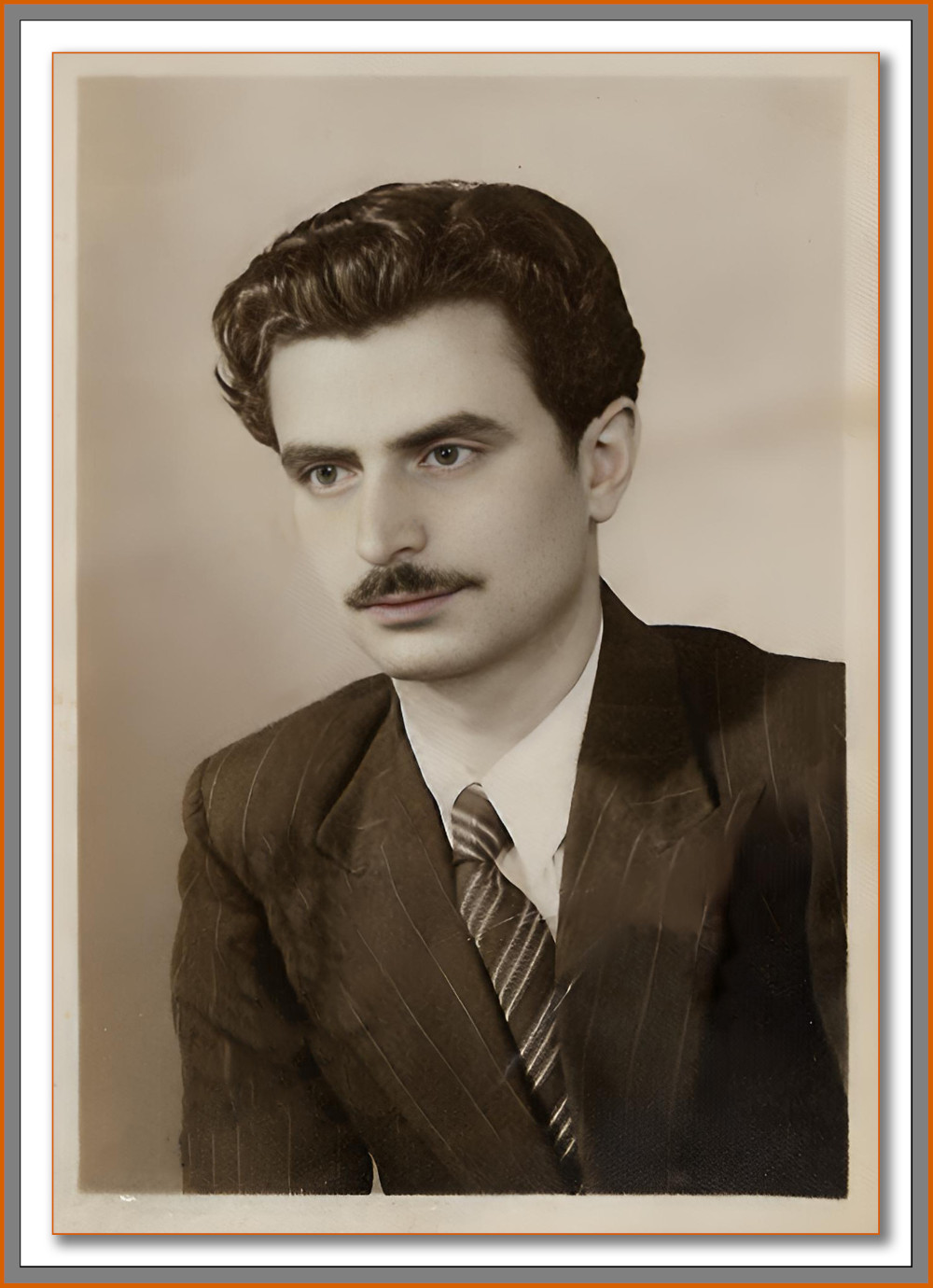

young Manohar Kaul, under-graduate college days

He later pursued a Master’s degree in Economics from D.A.V. College, Lahore. However, due to the communal riots during the Partition of India, he was forced to flee Lahore before completing his final examinations. It was only later, when a camp college was set up in Delhi by Punjab University, that he was able to sit for his exams and complete the degree. An interesting anecdote from this tumultuous period recalls how, as a college student in Lahore, he and several Kashmiri collegemates, while planning their escape during the riots, were given Gandhi caps and Fez caps by their elderly college warden. These were to be worn strategically when passing through areas populated by specific religious communities—a testament to the perilous and often surreal nature of their flight.

His formal art training was honed at the Sir Amar Singh Technical Institute in Srinagar, where he developed his foundational skills in drawing and painting. Kaul often spoke of four “gurus” who deeply shaped his artistic growth: Nature itself; his mentor, Shri J.C. Mukherjee, under whose guidance he studied for three years at the Institute; and Shri D.N. Walli, the lone landscape painter in Srinagar who introduced him to the clarity and freshness of watercolour.

He later appeared for the City & Guilds Institute (London University Examination) in Painting and was awarded a First Class—a distinction rarely achieved by Indian artists of his generation, marking him early on as a painter of serious academic merit.

Struggle and Emergence in Delhi

The tribal invasion of Kashmir in 1947–48 forced Kaul to leave his homeland and rebuild his life in Delhi. Though he came from a well-to-do family and had this advanced degree, the upheaval left him with little. A passionate painter since childhood, he took up small jobs and quietly offered his early watercolours for sale, often on the roadside or wherever he could find a willing viewer. Despite these hardships, his work began to attract attention from those who saw its sensitivity and depth. This period of hardship shaped his resilience and reaffirmed his lifelong commitment to art.

Around this time, he painted Amar Jyoti, a deeply emotional depiction of Mahatma Gandhi’s cremation. The work was exhibited at the Gandhi Mandap Exhibition and later gifted to the Gandhi Smarak Nidhi, a gesture that drew warm encouragement from Shri Devdas Gandhi, who urged Kaul to pursue his artistic path further.

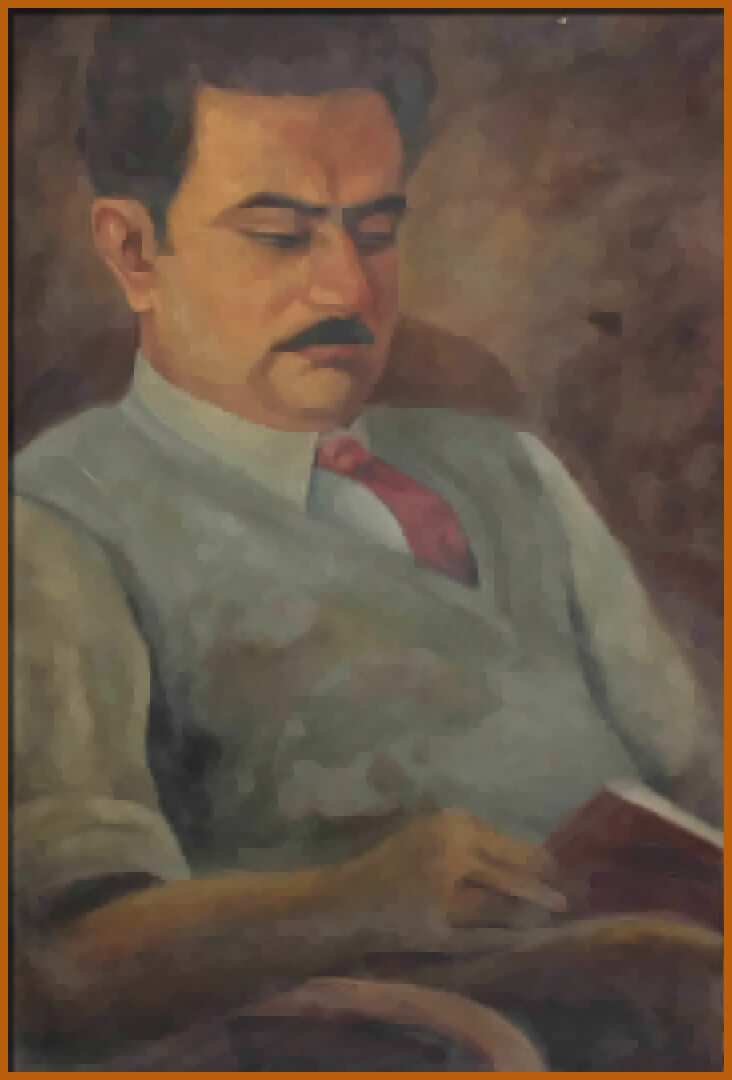

Self-portrait by Manohar Kaul, circa 1957.

In Delhi, he came into contact with Prof. M.L. Chawla, Director of the News Services Division, who introduced him to Dr. M.S. Randhawa, then Deputy Commissioner of Delhi. After reviewing Kaul’s paintings and writings on art, Randhawa helped him secure a post as Assistant Editor at Our India magazine, a journal published by Rambabu of Dhoomimal Gallery and edited by A.S. Raman. This role, however, was short-lived; upon securing a government position, he had to resign from 'Our India' due to regulations prohibiting dual employment. This marked the close of that specific professional chapter, though his engagement as a writer and cultural commentator continued to develop as a significant parallel aspect of his life.

Though he began his career as a bureaucrat in the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, his true calling lay in the arts—as a painter, writer, critic, editor, and profound cultural leader. Early in his government service, Kaul faced a significant hurdle: having painted numerous watercolours and amassed a considerable collection, he booked a gallery at AIFACS for an exhibition, only to be refused permission by his head office due to restrictions on government servants holding public exhibitions. Seeking assistance, he approached Shri J.C. Mathur, the Director General of All India Radio and a known patron of the arts. Thanks to Mathur’s intervention, permission was eventually granted. This incident became a pivotal moment, as it subsequently led to the removal of such restrictive policies, paving the way for government servants to freely pursue educational, cultural, and scientific activities in addition to their official duties. These years of emergence and exploration in Delhi were foundational in shaping the meditative and spiritually informed artistic style for which he would become renowned.

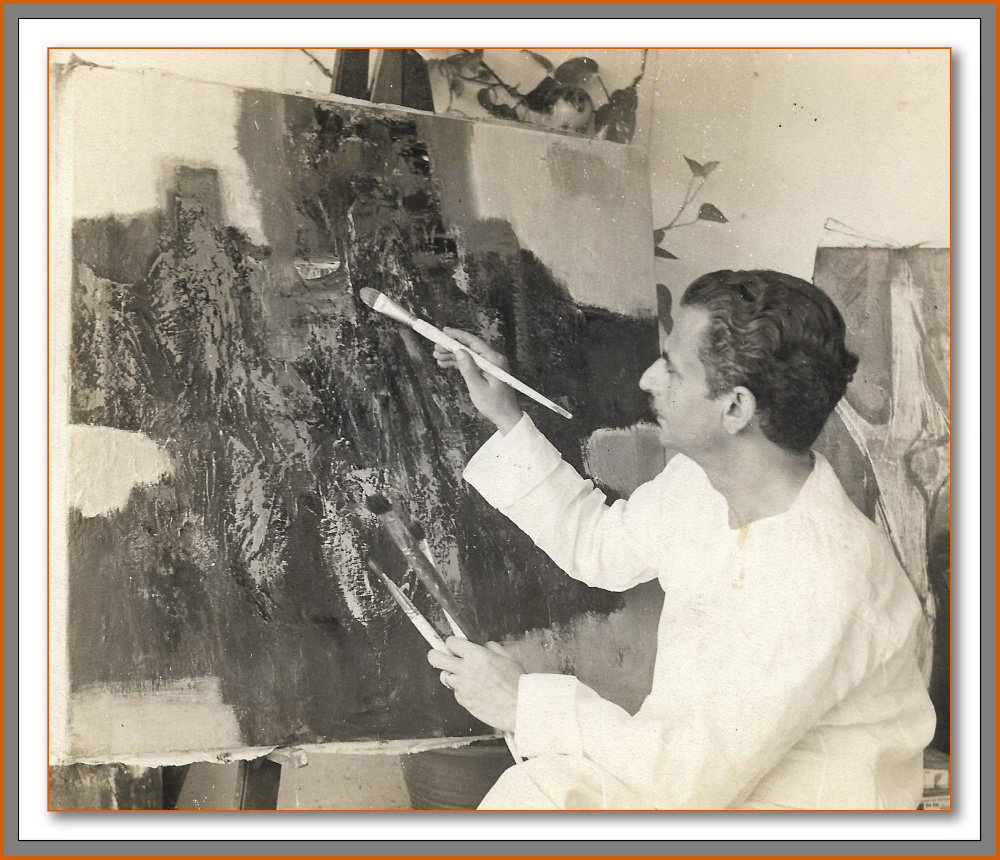

Manohar Kaul, painting oil on canvas

While taking on new responsibilities in the publishing world, Kaul remained deeply committed to his painting. Shortly after settling in Delhi, he came under the guidance of Shri Bimal Dasgupta, who introduced him to oil and later acrylic painting. The two became close friends, and Dasgupta took special interest in nurturing Kaul’s evolving technique and expression. Kaul held tremendous respect for him—not only as a mentor, but as someone he considered family, and he often referred to Dasgupta as the fourth of his four artistic gurus.

Artistic Vision and Practice

Manohar Kaul's artistic vision was deeply personal and meditative, often expressed through solitary painting sessions during amritvela—the sacred, predawn hours he considered most fertile for creativity. His landscapes are meditations: tranquil, mystical, and deeply rooted in Kashmir’s spiritual landscape. His luminous watercolours, particularly the Mystique of the Moon and Auras of the Dawn series, are celebrated for their serenity and spiritual character.

He was also profoundly interested in the healing power of color, exploring its emotional and curative potential in his later work. His exhibitions often featured newer watercolours based on color therapy—a field he studied deeply, believing in the emotional and therapeutic impact of specific hues and their resonance with both the human body and the natural environment. Beyond conventional artistic expression, Kaul’s exploration of color was profoundly intuitive and, at times, philosophical. He maintained a long-standing interest in astrology, viewing it not as superstition but as a symbolic system that illuminated patterns in life, nature, and consciousness. Though he may not have discussed it publicly, this interest quietly shaped his reflections on energy, color, and harmony, subtly influencing his later watercolours, which often suggest an inner resonance between cosmic rhythm and human feeling.

photograph of Manohar Kaul, 1994

Though he consciously avoided depicting violence or conflict, Manohar Kaul’s art was not apolitical. He believed that portraying the aesthetic richness of Kashmir was itself a form of cultural resistance. “I want to show everyone how beautiful Kashmir was,” he once said. “Only then will they get the strength to change it.” Even after settling in Delhi, Kashmir remained his creative homeland and spiritual wellspring. His paintings are held in prominent collections, including the National Gallery of Modern Art, Lalit Kala Akademi, Punjab Museum and Art Gallery, AIFACS, and the Ministry of External Affairs. He exhibited widely, including a major retrospective in 1983 showcasing over three decades of his work.

Cultural Leadership and Scholarly Contributions

Kaul’s legacy extended far beyond the canvas, as he played a crucial role in revitalizing Indian art discourse and institutions.

He was instrumental in revitalizing the All India Fine Arts & Crafts Society (AIFACS), serving as its Acting President and Chairman. He also served as Editor of Art News and Assistant Editor of Roopa-Lekha—two prestigious AIFACS publications—roles he held until 1990 and later helped revive during his stewardship at the institution. He later founded and edited the quarterly journal Kala Darshan – The Complete Magazine on Indian Art & Culture, a remarkable effort sustained solely through his own commitment and limited resources. With no institutional support or staff, Kaul personally handled every aspect of the publication — from soliciting articles and coordinating with artists and writers, to preparing mailing lists, packaging each copy, and transporting the bundles to the post office in a hired cycle rickshaw. He often lifted and carried the entire load himself, managing even the smallest tasks with little or no help. It was an uphill battle, driven entirely by his belief in the cause of Indian art and his unwavering dedication to fostering serious art discourse. In 1993, he guest-edited a special issue of the Lalit Kala Akademi journal, focusing on the Bengal School’s impact on modern Indian art.

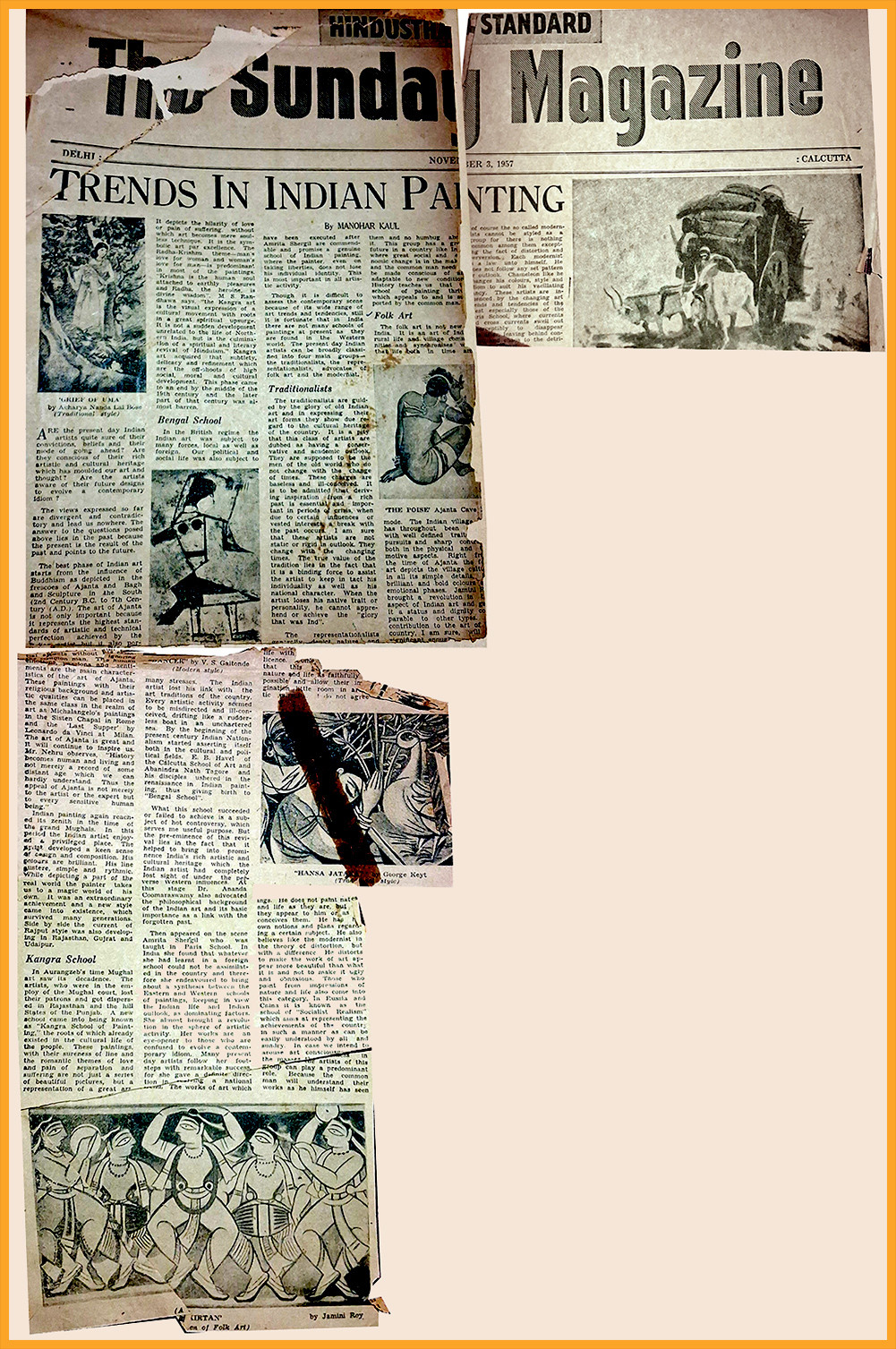

Hindustan Standard, November 3, 1957

Kaul’s critical writing career began in his early Delhi years, sparked when a journalist friend, part of the vibrant intellectual circles who regularly converged at the United Coffee House in Connaught Place, encouraged him to submit his essay 'Trends in Indian Painting' to The Hindustan Standard (Calcutta). To his delight, the essay was published in full, occupying nearly an entire page, inspiring him to expand it into a comprehensive volume—the first of its kind on the modern period. He later acknowledged the support and guidance of Dr. M.S. Randhawa and Shri K. K. Nair (Krishna Chaitanya) in shaping the book.

Although Kaul initially approached Dr. M.S. Randhawa, then President of AIFACS, to write the foreword for Trends in Indian Painting, complications arose. Randhawa was willing, but he requested that Kaul soften a few paragraphs that were critical of his close friends — Dr. Mulk Raj Anand and W.G. Archer — particularly regarding their interpretations of the contemporary art movement. Kaul, however, was unwilling to compromise the integrity of his critique and stood by his original text. As a result, Randhawa declined to write the foreword, not wanting to appear endorsing Kaul’s critique.

Though this was a setback, a friend later suggested he approach Dr. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, then Vice President of India. Radhakrishnan agreed, but only on the condition that the manuscript met his intellectual standards. After reviewing the text — which he kept for nearly two months — he was impressed enough to contribute the foreword himself, offering a significant endorsement of Kaul’s scholarship.

His scholarly contributions to Indian art history include:

- Trends in Indian Painting: Ancient, Medieval, Modern (1961), with a foreword by Dr. S. Radhakrishnan; republished in three volumes in 1999.

- Kashmir: Hindu, Buddhist and Muslim Architecture (1971), with a foreword by Dr. Karan Singh.

He continued writing art criticism for decades. In later years, he contributed reviews and essays to publications such as The Hindustan Times and Sunday Mail, maintaining a critical presence in both scholarly and public-facing art discourse.

Kaul’s commitment to the arts extended to significant organizational roles. He was a member of INTACH, served on the Resource and Advisory Committee of Sahitya Kala Parishad (1987–1988), and was part of the Selection and Purchase Committee of Jawahar Kala Kendra, the Kala Melas, and the 8th Triennale–India. Furthermore, he chaired the First World Art Conference (AIFACS, 1977), which saw participation from 29 countries, with Kaul chairing most of its sessions. He also took part in numerous seminars—including one on Nicholas Roerich organized jointly by the Sahitya Akademi and Lalit Kala Akademi.

Personal Influences and Legacy

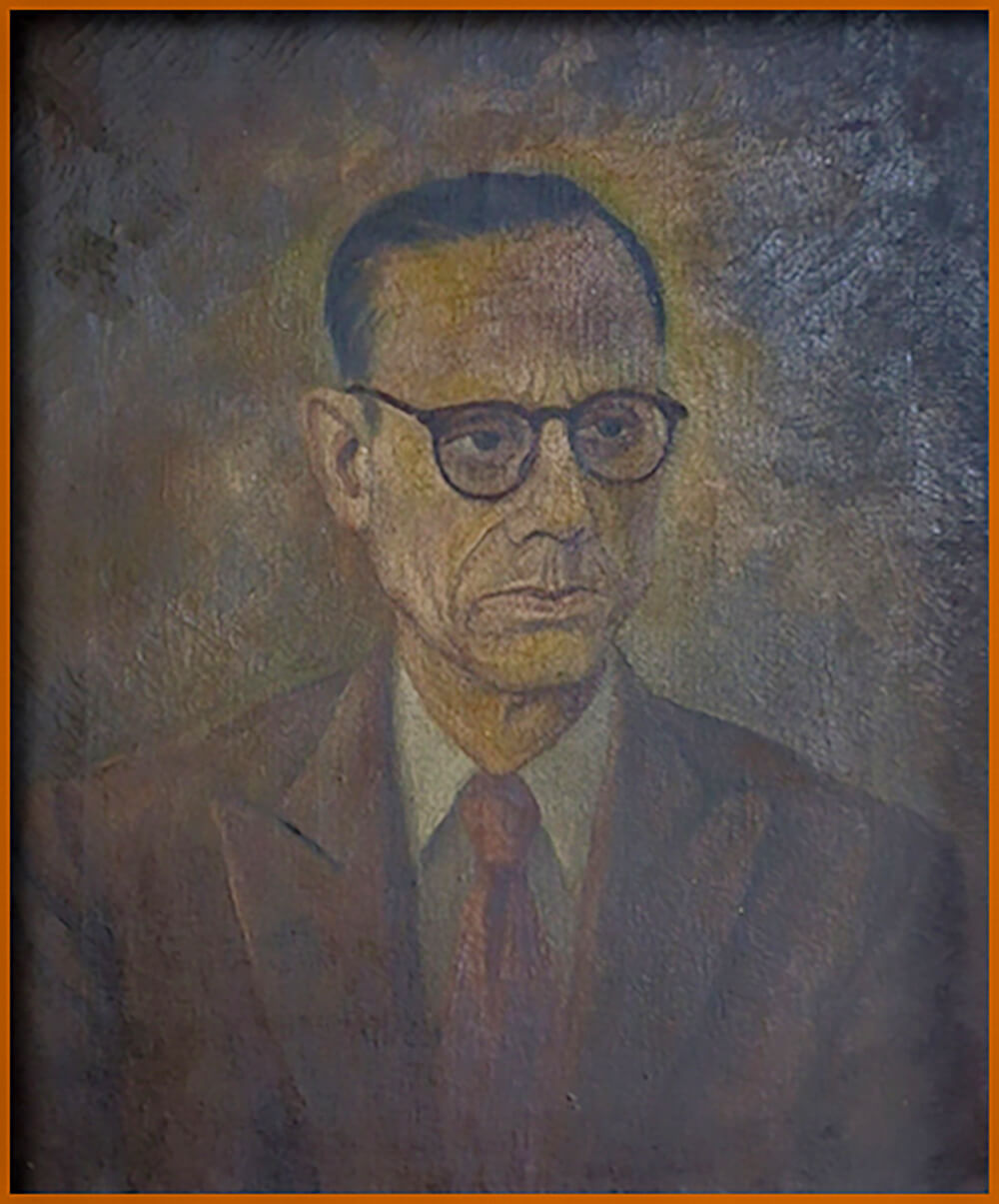

Portrait of Kanth Kaul, painted by Manohar Kaul.

Manohar’s sensitivity to art and aesthetics was shaped early on by his father, Prof. Kanth Kaul, a deeply learned and spiritual figure. Among the first in Jammu & Kashmir to earn a Master’s degree—likely around 1918 from Calcutta University—Prof. Kaul taught English literature at S.P. College, Srinagar, where he also served as librarian, curating the institution’s rich collection of books and manuscripts. He later held a librarian position at the Hindustan Times in Delhi. A man of literary depth and philosophical inclination, he played a central role in nurturing Manohar’s intellectual and artistic development, instilling values of reflection and inner discipline. Prof. Kanth Kaul's influence also extended to the literary sphere; he edited the magazine 'Art & Culture,' produced by Dhoomimal Gallery. Manohar Kaul contributed to this publication, assisting his father in collecting material and writing for it, further solidifying his early connection to the art world through his family.

Beyond his academic and literary pursuits, Prof. Kaul was deeply spiritual. He was a disciple of Swami Purnanand Giri, a revered ascetic of the Shivalaya at Bengali Mandir, Rishikesh. This grounding in spiritual thought profoundly shaped Manohar Kaul’s own orientation toward solitude, silence, and meditative practice—qualities that would later define his art and life philosophy.

Manohar Kaul’s creative and intellectual lineage also drew strength from his great-grandfather, Shri Sahajram Kaul, known as “Khazan” (Treasurer). A scholar of repute, he wrote poetry in Persian, Urdu, and Kashmiri, and was deeply learned in astrology, having authored several works on the subject. His poems were published in Bahaar-e-Gulshan, a celebrated anthology of Kashmiri poets, both classical and contemporary. Known across the region as a respected astrologer and literary figure, Sahajram Kaul embodied the syncretic scholarship that would echo through his great-grandson’s art and thought.

Photo of Mohini Kaul, August 2005.

Equally vital to his life and work was his wife, Mohini Kaul, whose quiet strength and unwavering support sustained him throughout his journey as an artist. In their early years, while living in modest apartments, she gracefully adapted to their living room doubling as his studio—never once complaining, even as she cleaned his oil brushes and palettes herself. She managed the household and family life with poise and quiet strength, creating the stability and space he needed to pursue his work without distraction—a devotion he acknowledged often, and with deep gratitude. She lived on for sixteen more years after his passing in 1999, holding his memory close and continuing their shared journey in spirit until her own death in 2015.

He was averse to salesmanship and self-promotion, often saying that painting was a meditative practice, and that his true reward lay in the peace and fulfillment it brought. In an art world increasingly driven by visibility and market value, Kaul remained steadfast in his belief that sincerity and solitude were essential to true artistic expression. He generously mentored younger artists, offering support and guidance with whatever resources he had.

Though his works were sold—many finding their way into private collections, museums, and galleries—Kaul showed little interest in marketing, pricing strategies, or cultivating collectors. Sales happened organically, prompted by viewers moved by his art. As his family affectionately joked, despite holding a Master’s degree in Economics, he remained untouched by even the “E” of economics—a gentle reminder that his detachment from commercial concerns was deliberate, not from ignorance.

Manohar Kaul’s contributions were recognized with several honors, including the Jammu and Kashmir Cultural Akademi Award (1965) and the title of Kala Vibhushan from AIFACS (1988). He also shared his deep understanding of art history and aesthetics as a visiting lecturer at institutions such as Bhartiya Vidya Bhavan and the College of Art, Delhi.

Manohar Kaul’s paintings, writings, and institutional legacy endure as a testament to a life grounded in stillness, cultural memory, and a profound reverence for beauty.