Auras of Dawn: Watercolours of Silence and Light

New Delhi, 1994–95

Presented at AIFACS in the closing days of 1994, this exhibition brought together a series of watercolours where the auras of dawn drift through landscape and memory. Kaul’s images do not so much describe as breathe—dissolving form, softening space, and evoking the meditative stillness of Kashmir’s mornings. Each painting lingers like a recollection: half-revealed, half-remembered.

To accompany these works, the exhibition also included a focused selection of Kaul’s earlier oil paintings, creating a mini-retrospective that illuminated continuities and transformations across his practice.

Catalogue

Press Reviews

FEATURES / NATION

ART-The Statesman, Tuesday, December 27, 1994

This piece was Kaul's last one. May God help him to rest in peace – Signed: Manohar

Divine Susurrus and Hum of Light

By K. L. Kaul

Manohar Kaul’s watercolours (on view at AIFACS) explore a quiet musical movement — the soft, subtle gestures of light at dawn across the Kashmir landscape. This sacred time, known as Prabhat Vele, is the silent stirring of the earth’s soul. It is when the spirits of the years and the spirits of the earth come together in immaculate harmony, participating in a daily act of devotion — witnessed by tall, sleepy poplars and bushy willows, standing like sentinels.

This marks another nostalgic return to roots by a Kashmiri artist — this time, a 70-year-old veteran. Significantly, it reflects a return to purity, to a broad, inclusive outlook, to universalism and positivism — a counterpoint to the recent times of divisiveness and spiritual confusion.

Manohar Kaul has always been dedicated to Kashmir and its deep spirituality. All his earlier exhibitions confirm this. But the spirituality in his previous works had a different quality — filled with sparkling, cheerful images. His compositions were always a dialogue between the physical world and the spiritual, whether floating above or hidden beneath.

In these recent works, we encounter glowing, glimmering pools of light emerging from the deep, evocative darkness of the Himalayan interior. Light appears in its primal moment — new to the world, coaxing memory from the caves of night, reuniting the threads of time, and re-establishing cosmic order. The artist repeats these “musical moves” of light, as though retracing the passage to reinforce the ongoing cycle of being and becoming.

When we sleep, our ties with the world are temporarily severed. Ancient Kashmiris believed this happened to the universe itself — and that music, especially the image of music, could help restore those connections. The healing process begins in the pre-dawn hour as light quietly re-enters, awakening memory and reconnecting life with both yesterday and the distant past.

Memory has always held a privileged place in history. The Greeks considered Memory the mother of all nine Muses. Lord Krishna also emphasized its importance — its loss leads to the destruction of buddhi (intellect), then action, and eventually collapse:

"Smriti bhramshad buddhi nasho, buddhi nashat pranashyati..."

(From loss of memory comes the loss of intelligence; from the loss of intelligence, one is ruined.)

The musical image has often been considered magical — particularly in its power to restore memory. Hence, music in such processes is sustained and prolonged (sostenuto).

Among the many spontaneous and varied images in these watercolours, there are those that show the artist’s personal leanings — his aesthetic and philosophical outlook. Light often becomes a molten pool over what, in daytime, would appear as a saddle between mountains. At times, it loops and turns into a halo in the center of a dark water channel — a path known to pilgrims, as it leads to shrines on either side.

Light struggles to rise from beneath a bridge, leaving the darkness behind. Occasionally, it takes on almost human gestures — stepping forward to kiss a snowy patch, tiptoeing down the slope, slipping into a deep depression, then forming a soft pool behind clouds, before charging gleamingly into the trees below.

THE TIMES OF INDIA, January 6, 1995

Kaul Brings Alive a Vanished Kashmir

By Ratnottama Sengupta

“What it be sea, land, or sky?

he praise the beauty of the wind

among derelict fields,

or kneel before the breathtaking spirit of silence

reigning supreme in the downward dive of a snowy giant’s height?”

The poet in Keshav Malik penned these lines for Manohar Kaul. Both men treasure memories of their youth spent in the valley at the foothills of the Himalayas. Kaul recalls rowing with friends on Dal Lake — "and before we realised, it was two in the morning!" The icy stream filling the stillness of the luminous night; the rows of chinars standing guard on the horizon; the silvery crest of a crescent moon; the world bathed in the purity of snowflakes — for them, paradise needed no other name.

Decades down the winding course of life, Kaul now draws upon these memories of the ethereal landscape that was once his home. The valley lives on in its pristine glory: the woodlands have not lost their leafy haze, and the misty mountains remain suffused with tranquillity on the canvas of this artist now approaching 70.

After contemplating the Mystique of the Moon, his watercolours now celebrate Auras of the Dawn in Kashmir. Both series are fruits of Kaul’s communion with nature — recollected in tranquillity and reproduced from imagination.

“If earlier I used the watercolour medium to recapture nature transformed by moonlight,” says Kaul, “the current works are imbued with the meditative spirit of the daybreak hour.” This theme holds personal significance for Kaul, just as it did for the sages of old: “All along my creative years I have worked at this amrit vela (peaceful hour) when the atmosphere is fresh and undisturbed.”

While viewing the series at AIFACS, one may wonder why there's no trace of nostalgia or sadness in the works. It seems only natural for someone who roamed the Valley in its green glory to feel anguish now that it stands scarred and pained. Should not an artist’s soul reflect the trauma of a land in turmoil?

“No,” asserts Kaul. “That is the task of a reporter, an illustrator. I cannot paint a man killing another man.” But if he cannot show death, he can still depict the dream — a dream that may dissolve in the harsh glare of reality. “And yet,” Kaul hopes, “if people see how beautiful Kashmir is, their desire to preserve it may be strengthened.”

Since retiring from government service in the 1980s, Kaul has been based in Delhi and creatively engaged with the city. Almost single-handedly, he has brought out the art journal Kala Darshan. “I have even been the errand boy,” he says with a smile.

The effort has borne fruit for the art world: under his leadership as Chairman of the All India Fine Arts and Crafts Society (AIFACS), Roopa-Lekha, the Society’s journal, has been revived. Four galleries once abandoned by artists are now among the Capital’s finest. The Society’s coffers are healthy, and there are plans for a library and conference hall “like at the India International Centre.” The Society has expanded to Ghaziabad (for graphic artists) and Chandigarh too. Studio spaces for artists — for six months at a time — are on the anvil. Most significantly, senior artists over 60 are now being honored with a modest grant of ₹3,000 per annum.

All this — for the world of art.

And in the small hours of the morning, before the world makes demands on Manohar Kaul, there remains the divine landscape — the one he carried within him when he left Kashmir behind.

As a bureaucrat in the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Kaul had returned to Kashmir in the early ’70s. “I could never have imagined that the same men who watched the surrender of General Niazi without sorrow could one day pick up the gun!” he says.

“Perhaps for money. Perhaps for pride. Perhaps because of pain passed down through generations.” His voice carries a hint of remorse.

Kashmir, to him, was not just paradise on earth — it was a land of great strategic significance, bordered by China, Afghanistan, and the newly formed Pakistan. The guardians of India’s interests thus deemed it vital to hold on to Kashmir “at any cost.” A cost, Kaul notes quietly, “we are still paying for.”

ART & ENTERTAINMENT

THE HINDUSTAN TIMES

New Delhi, January 3, 1995

Watercolour by Manohar Kaul

By Buddha Dev Malakar

Manohar Kaul’s mountain landscapes in watercolour (on view at AIFACS) offer a refreshing experience to anyone who has grown weary of the glut of "modern" art — or what often passes in its name.

Titled "Auras of the Dawn", the exhibition evokes the exquisite moments just before or after dawn — that quiet hour when the sun breaks through clouds gathered during the night and casts its light on a pool of water, creating a magical and translucent, though transient, effect.

Blues, browns, and greens are applied spontaneously or left untouched between intermediary spaces of white, creating a luminous light effect — a truly joyous experience, especially in today’s world of movement and turmoil.

Mountainscape No. 20 stands out as a serious work: mountains flanked by trees on both sides with a pool of water in the foreground. This results in a centralized composition which, though traditional, offers a quiet and deeply aesthetic joy.

New Delhi, 27 December 1994

सीध

बश से

आकृतियां उभर उठती है

By mitilesh Srivastav

Exhibition Highlights

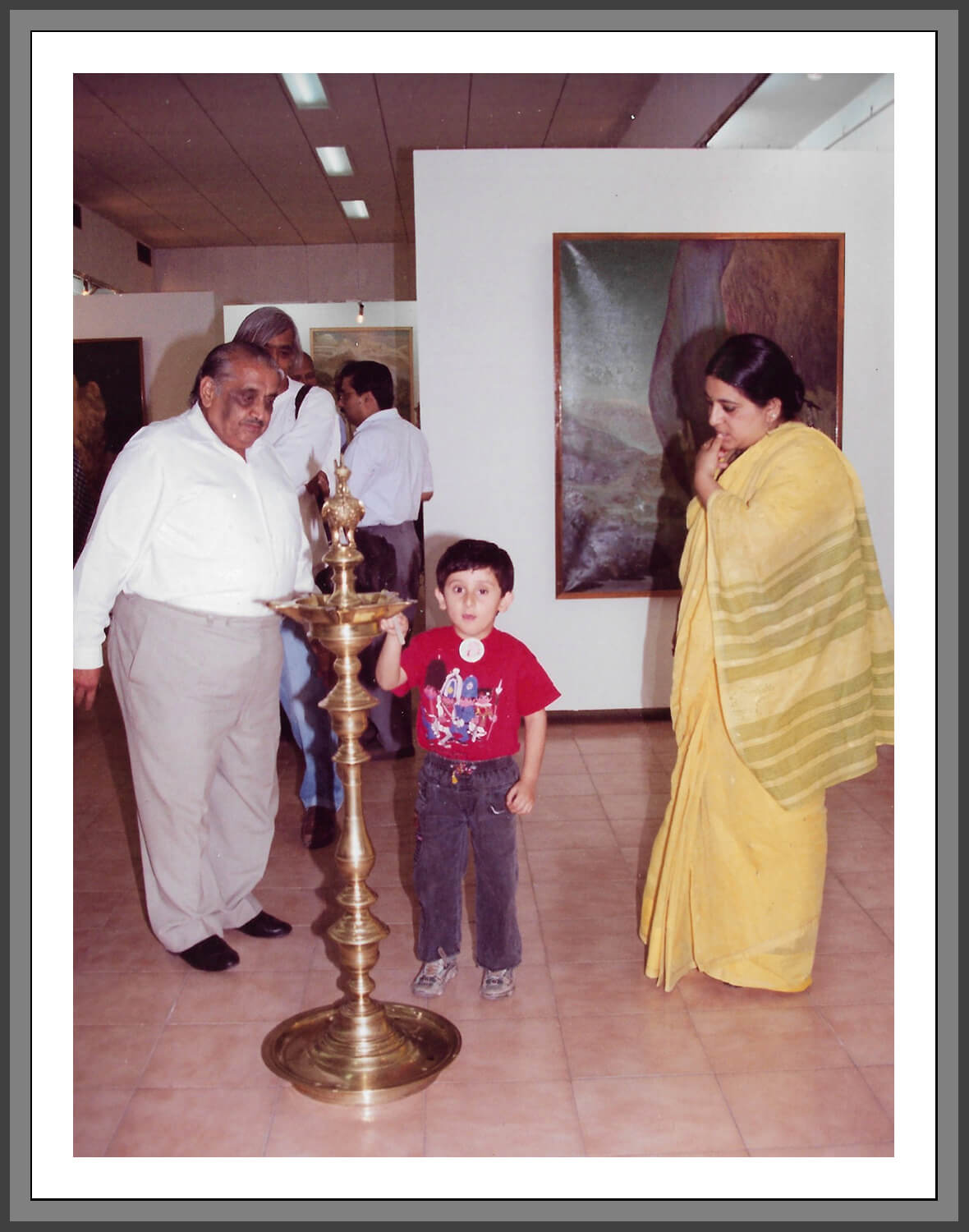

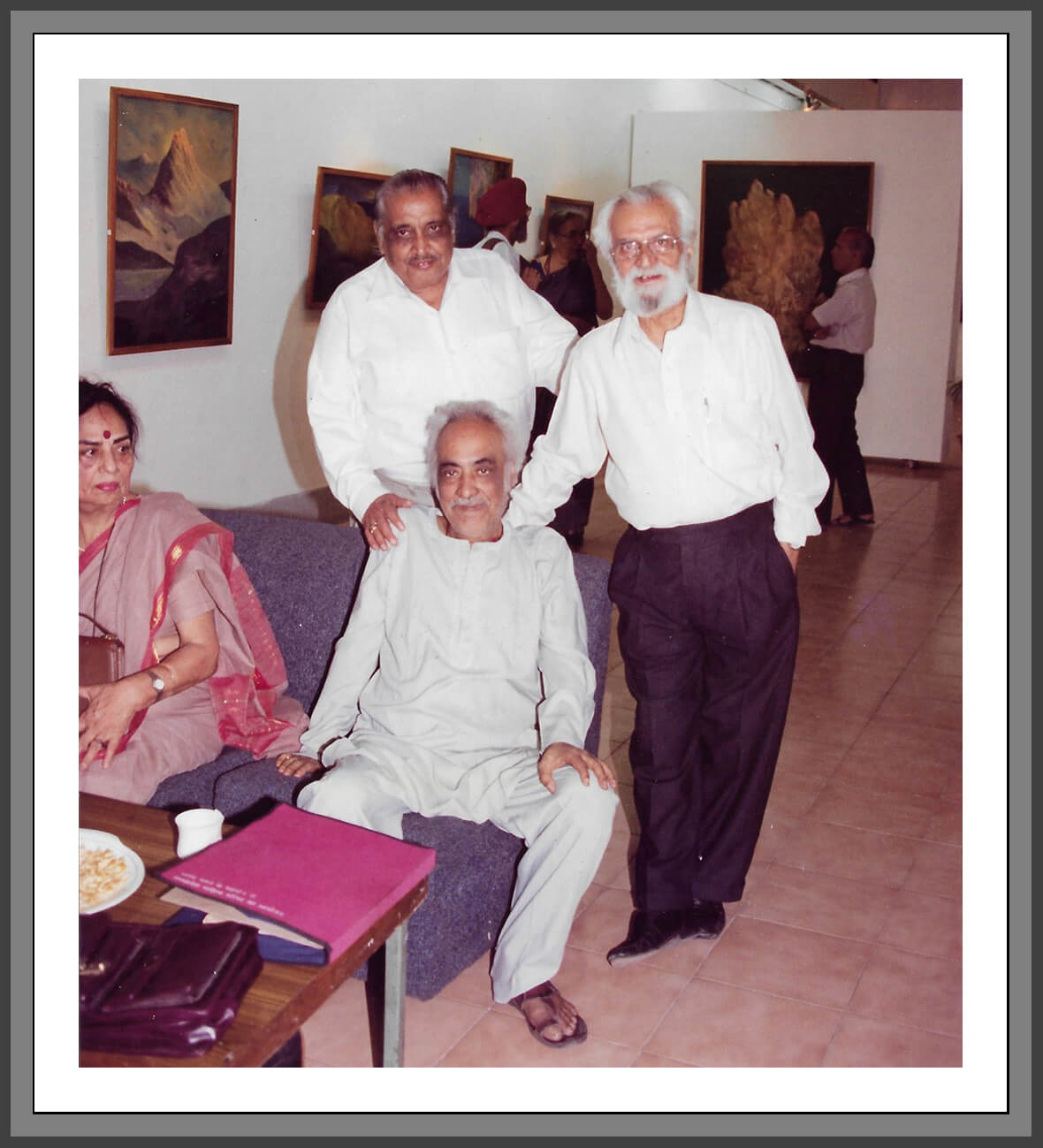

Archival photographs from the 1994-95 exhibition of Manohar Kaul’s Watercolours: Auras of Dawn & mini retrospectiveof oil paintings, capturing moments with fellow artists, eminent guests, family, and friends who came to view the work.

![[Caption needed]](/paintings/exhibitions/1995/exhib1994-4.jpg)

![[Caption needed]](/paintings/exhibitions/1995/exhib1994-6.jpg)